Some images of women in Ukraine have gone viral in the past week. But what do these specific images add to the narrative surrounding the Russian invasion and what of the women who don’t fit the media image of the “ideal” female?

In the immediate aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the internet turned into a sped-up meme factory.

From Facebook to Instagram to TikTok, social media has been flooded with memes giving form to our view of the war, and they have become essential tools in opinion-forming. Indeed, the mainstream media has, in turn, taken up these memes and images and broadcast them around the world.

A quick look at what is going viral shows accounts of brave civilian resistance by the Ukrainian people. Amongst this meme category, the imagery of women is particularly striking.

Take for example, the Ukrainian MP Kira Rudik, whose image of herself holding a Kalashnikov has been wildly popular online. Originally posted to her Twitter handle, the post has spawned multiple headlines.

Rudik is pictured in her home, barefoot and in day clothes. The contrast between the casual setting and her holding a firearm, an indication of bracing against possible violence to come, is sombre.

She looks bracingly into the camera, her expression embodying the caption she later chose to go with her picture: “Our women will protect our soil the same as our men.” A female politician taking on a “male” role. Women and men are hashtagged, meaning they become key terms.

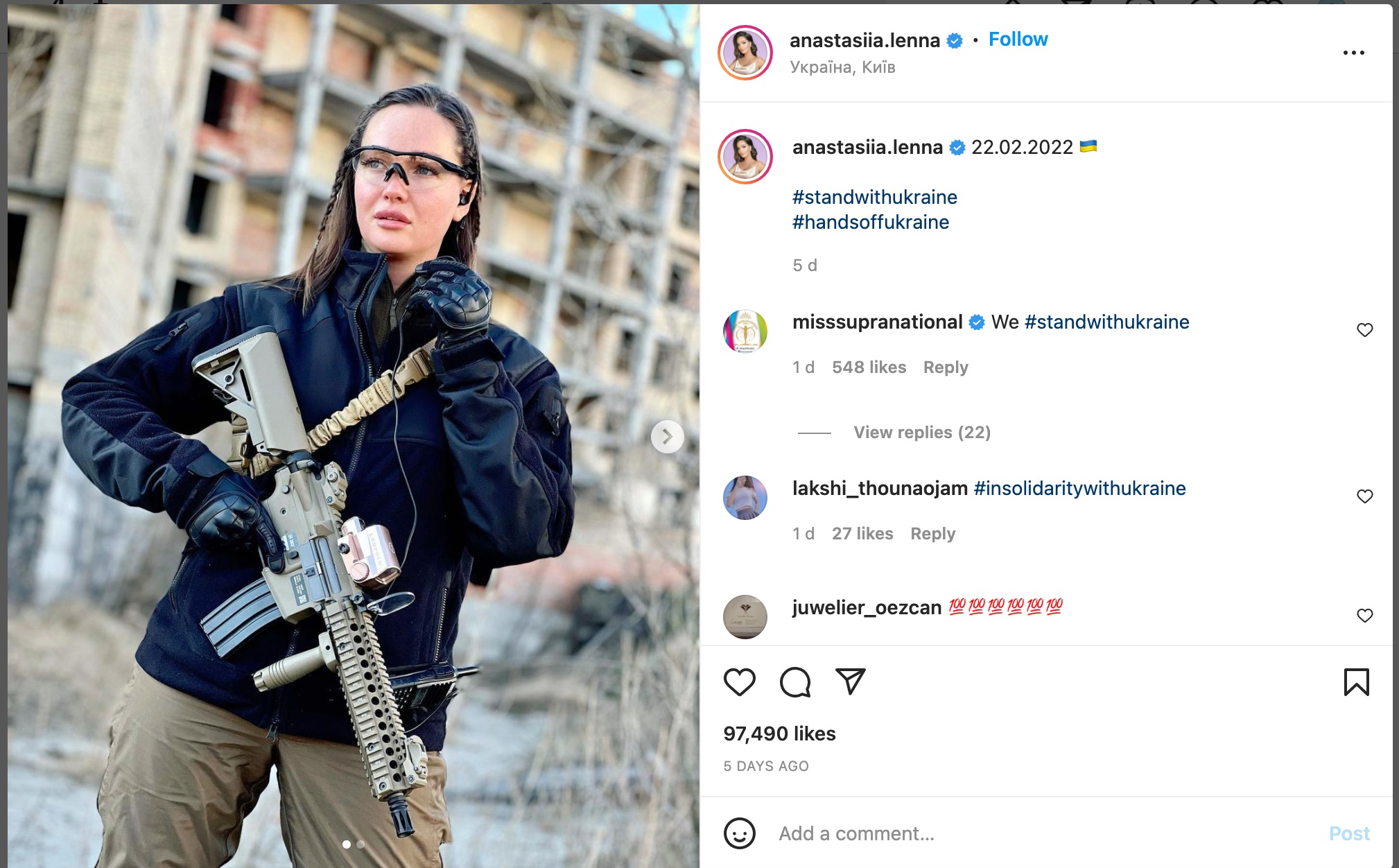

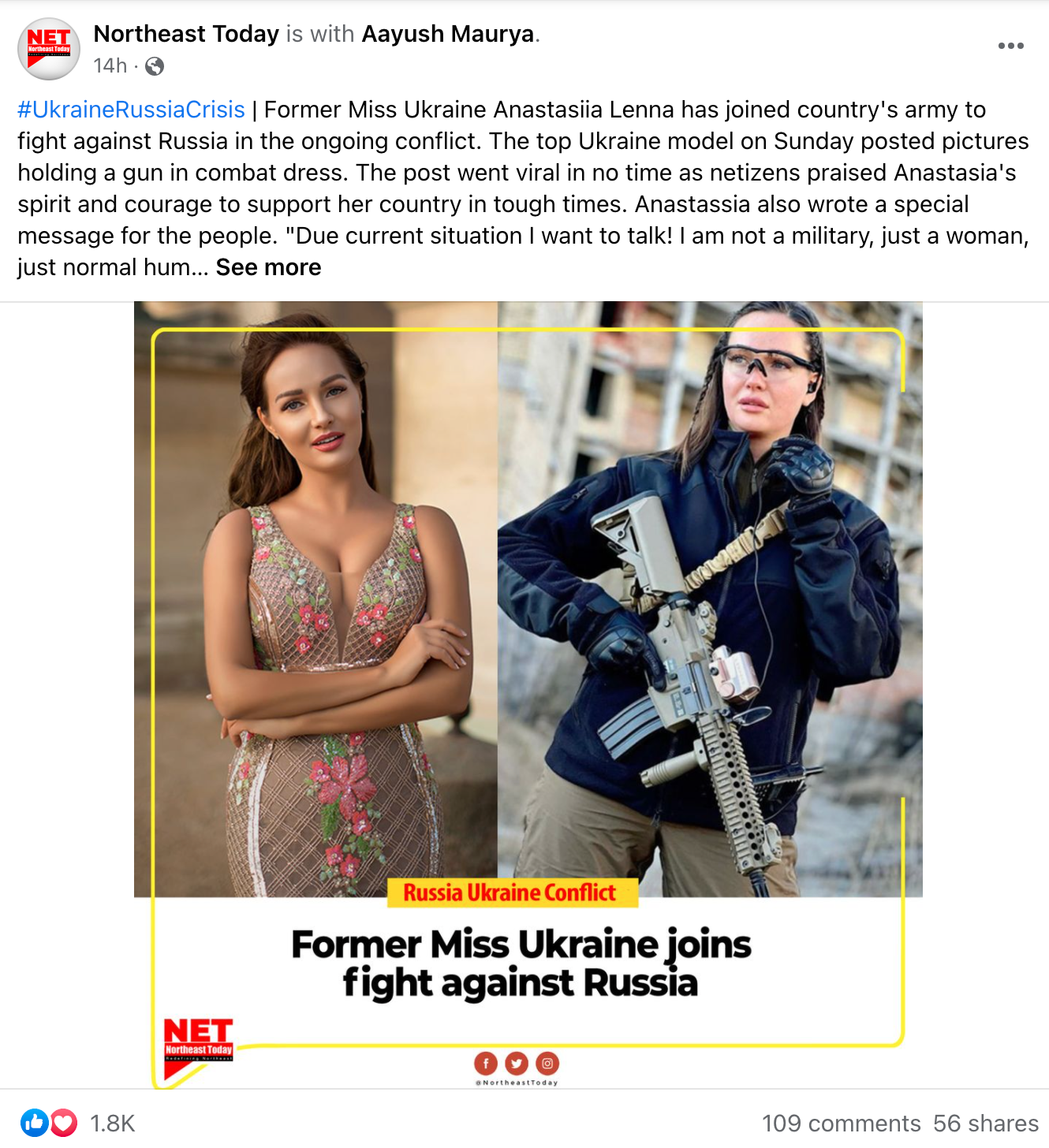

Similarly, images of former Miss Ukraine 2015 Anastasiia Lenna holding a gun have also gone viral. She originally posted two pictures on her Instagram account, in military clothing and holding a rifle.

Edited pictures of Lenna that splice together these photos with old images of her are doing the rounds in online articles and on social media.

The older pictures present a completely different persona: a model and beauty pageant winner in heavy makeup and feminine (often revealing) clothes.

Comments underneath all these posts applaud Lenna, who herself probably understood the power of the image she was posting.

Is this inherently harmful? Should we exercise more caution when it comes to using images of female resistance to oppression?

Lenna’s own post expressed patriotism and capitalised on it - both valid stances, coming from an influential Ukrainian woman whose livelihood depends on being in the public eye, and whose country is at war.

However, the images which have been circulated by media outlets hold elements of fetishisation based on her appearance and the fact that she is a woman.

The edited images almost all present a dual image: on one side, a selection of Lenna in figure-flattering clothing and bright colours to emphasise a specific idea of femininity, and that she is a “beauty queen”; on the other side the sombre beige and black of military garb, gun in hand, a woman in a man’s world and all the more to be applauded for it.

Whoever edited these pictures understood the visual mechanics of internet virality: woman, light-skinned, visible body, war, Ukraine.

It is a simultaneous fetishisation of the “ideal” female body - in this case fair, blonde, attractive, toned, lean - and idealised war through “civilised” (read “white”) resistance.

This can also be seen when images of white, blonde young female members of the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) holding guns and dressed in army fatigues have been circulated. These posts are uploaded mostly by women on their own social media handles. The IDF does not have an official stance on the posts, but has re-shared them on its official accounts and they are wildly popular.

These “IDF hotties” presented an image of TikTok dances, patriotism, thirst traps (sexualised images posted online) and the internet’s version of the “ideal” female. Both these examples illustrate that certain media outlets know how to use visuals of women to their advantage, to achieve user engagement and attention. Here is one example:

Consider another contrast: What kind of woman does the internet laud for being in the public eye? What would the reactions be if women in Yemen, Libya, Syria, Iraq, Palestine and Afghanistan appeared in images holding guns?

How would the image of a dark-skinned woman, wearing a hijab and holding a gun, be treated in the West? It would likely be instrumentalised, seen less as resistance and more as further proof of aggression and violence in the region. She might even be referred to as a “terrorist” or a “militant”.

This is the fundamental double-standard of the colonial and imperialist gaze; when one side does it, it is defence and bravery. When the other side does it, it is chaos and misrule, a danger to the “civilised” world, and further reason for intervention (military, political, and ideological).

Here, resistance narratives are being used for internet popularity - no surprise in an age of fake news. The image below, for instance, is of a young Palestinian girl called Ahed Tamimi. She became a symbol of Palestinian resistance, shouting and slapping armed Israeli soldiers during a protest in 2017. Tamimi was later imprisoned for eight months for other actions.

Tamimi is a contested figure, with some attributing her initial fame to her appearance: she had features that were familiar to Western audiences. Here was a child with fair skin and blonde hair; she could be North American, she could be European, she could be one of “us”. Somehow, Tamimi was less “other”, and therefore more deserving of sympathy.

Recently, the image has been posted again, with the false claim that it depicts a Ukrainian girl standing up to a Russian soldier.

Posted to TikTok, this image has garnered almost 700 thousand likes with people presumably taking it to be true despite the image showing a semi-arid landscape and a child in summer clothes. It is currently winter in Ukraine, and the average temperature in February is 2.5 degrees.

The re-emergence of this image in the context of the invasion of Ukraine may be deliberate, in order to gain likes. It is a prime example of how both media outlets and audiences should be critical of things they see online.

It is precisely Tamimi’s white-passing appearance that allowed her original image to be manipulated and included (largely unquestioned) in the current narrative of Ukrainian resistance.

The irony is unmissable: a Palestinian child’s image being used to supplement the narrative centring an Eastern European country, literally erasing and distracting from the original context of the image and the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine - a situation that many Western media outlets are hesitant to even call “occupation”.

How can the media better present women in times of conflict?

The war in Ukraine presents an ideal opportunity to highlight stories from different demographics and social groups.

What media outlets can do is avoid fetishising women in particular, for example by centring their words and actions rather than their bodies.

In the case of Kira Rudik, for example, some media outlets sensationalise that “this is a woman with a gun”, whereas others have reported the same story without centering the fact she is a woman. Instead, her position as an MP is usually mentioned. This person’s resistance is not limited to the confines of their gender, and their bravery is not limited only to holding a firearm.

Therefore, the media should redefine what bravery and resistance mean- and how these ideas are proliferated. There are many forms of resistance that people - particularly women - have displayed in times of conflict.

An image of an elderly woman on the Moscow underground is a poignant example: in an act of everyday resistance she wears the colours of the Ukrainian flag in a public space. Her presumably being Russian adds nuance to current media narratives: many Russians, too, are opposing the invasion and their own government.

Whether that means children who throw rocks at Israeli soldiers, or the female politicians and journalists of Afghanistan, or the many everyday acts of survival and resistance by Syrian people in refugee camps all over Greece and Turkey.

It is also important to avoid having selective sympathy and double standards when reporting on different communities undergoing war and conflict. Just as political crises may not be the same, human suffering and bravery (and “civilisation”) do not exist on melanin-toned scales.

Who gets to be brave?

In recent media coverage relating to Ukraine, a rifle in the hands of a fair-skinned and light-haired woman, defiant in her support for her country, is seen as an symbol of bravery and especially, female bravery.

It is interesting that women taking up arms is the criteria for bravery, as though only by replicating the position that men have traditionally occupied in war can women contribute to resistance.

Women have always resisted war and contributed to the political landscapes of their countries, even if the methods they used were immeasurable by the usual yardstick of masculinity.

In the hands of a European woman, the Kalashnikov that is a symbol of the masculinity and terror of the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan quickly neutralises. Mujahideen, it turns out, is a very different word from freedom fighter after all.

As with all human conflict, the war in Ukraine merits extensive coverage. This needs to be sensitive, free from the orientalist, racist, and sexist tropes that some coverage falls into.

And this attention, sensitivity and dignity are equally deserved, for example by the people of Yemen, Palestine, Syria, the Uyghur people, the Rohingya people, who the world forgets because of their skin colour, or religion, or their passports.

Let us not be selective with our attention and empathy.