Despite an unprecedented global flood of information, journalism remains strikingly impotent in confronting systemic crises—largely because the dominant Anglo-American model, shaped by commercial imperatives and capitalist allegiances, is structurally incapable of pursuing truth over power or effecting meaningful change. This critique calls for dismantling journalism’s subordination to market logic and imagining alternative models rooted in political, literary, and truth-driven commitments beyond the confines of capitalist production.

The contemporary global landscape is defined by a deep dissonance: despite an unprecedented massive global flow of information, journalism appears fundamentally unable to effect any concrete change on the ground. World populations are currently witnessing the intensification of ‘modern pathologies of democratic capitalism’: rising inequalities, far-right violence, armed conflicts, environmental degradation, and polarization—all phenomena richly documented yet persistently unresolved. This systemic impotence signals a profound failure of the dominant paradigm: the Anglo-American journalism model.

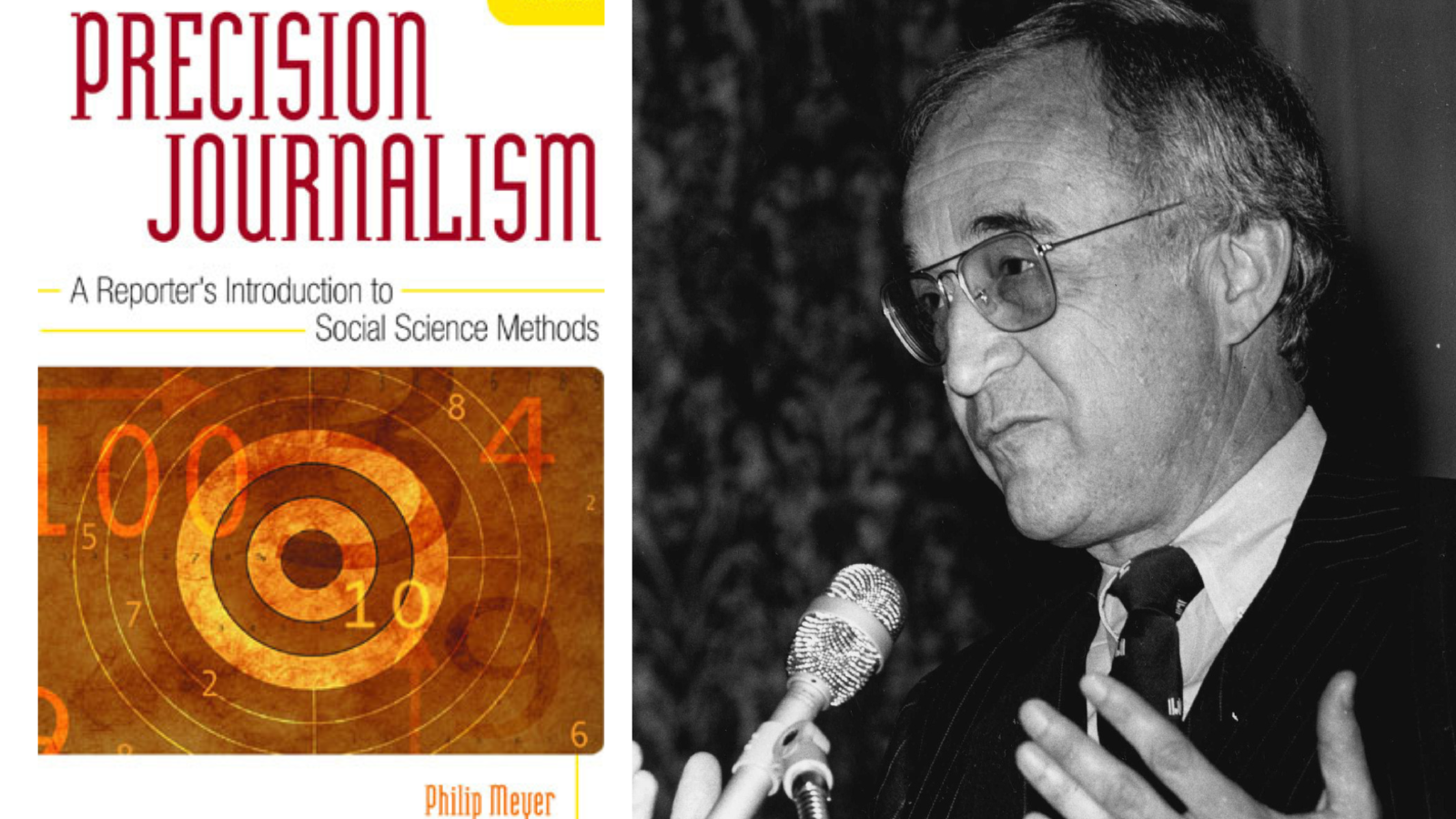

We contend that this failure is not incidental but structural, rooted in the model’s very genesis as a business enterprise embedded within capitalist production, circulation, and consumption of news. The Anglo-American journalism tradition, which originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, owes its character to aggressive commercialism. This commercial imperative gave rise to practices such as the inverted pyramid style and necessitated the adoption of ‘objectivity’, a principle that American sociologist Gay Tuchman defined as a ‘strategic ritual’ intended to protect “newspapermen from the risks of their trade.”

The militant spread of this model—via journalism schools, textbook publishing, wire services like the Associated Press and Reuters, the status of English as a world language, and the hegemony of the American state after the Second World War—has imposed its characteristics globally, often flattening the significance of varied traditions, such as the ideological and literary focus of European journalism or the hybrid systems seen in regions like the Indian subcontinent.

We assert that the dual role of news media—as keepers of public interest and means of pursuing profits for corporate owners—creates what Pamela Taylor Jackson terms an unavoidable “clash of capitalist and journalistic imperatives.” Ultimately, journalism is perpetually condemned to “subordination” by an economic rationale of marketing. This systemic compromise ensures that the news output, regardless of its volume, functions primarily to generate content and attractive frontpages to feed the global advertising industry. We argue that by prioritizing facts “manufactured in corridors of high power” and consecrated by official sources, the Anglo-American journalism model functions to perpetually justify the existing order, instead of pursuing truth value or challenging the structure of power.

Defining the Anglo-American Paradigm

The Anglo-American journalism tradition is associated with several core characteristics. Firstly, it places journalism as a distinct category, separate from the fields of politics, literature, and religion, requiring journalists to assert a professional identity and maintain distance from party politics. Secondly, it is centered around what Scandinavian scholars, Svennik Høyer and Horst Pöttker, call ‘the diffusion of news paradigm’, which is structured around five elements: the event, news value factors, the news interview, the inverted pyramid, and journalistic objectivity.

As American professor Michael Schudson observes, aggressive commercialism in the 19th-century American press “was an important precondition for modern notions of objectivity and fairness.” This commercial success allowed the press to develop separate revenue streams through advertisements, fostering independence from overt political party control. However, this independence merely shifted allegiance from political masters to commercial masters. Some American researchers, focusing only on this success, flatten journalism into an Anglo-American invention, ignoring the many permutations across the world.

In contrast, the European tradition was associated with its ideological, political, and literary pursuits, often favouring advocacy. In 19th-century European countries like France, Italy, and Germany, journalism was heavily embroiled in politics and literature, featuring principal figures who were great novelists, such as Victor Hugo, Honore de Balzac, and Emile Zola.

Beyond this American/European binary, global media systems are incredibly varied. State-led or authoritarian models, such as those in the Gulf States and China, present the media as an extension of social control and governance. East Asian journalism, as seen in South Korea and Japan, often blends professionalism with cultural values, integrating commercial structures with societal values of peace and institutional trust. The Indian subcontinent provides an illustration of a hybrid arrangement, combining Anglo-American commercial news packaging with strong influences from regional identity, linguistic diversity, and political patronage. Developmental journalism, which prioritizes modernization, education, and national unity over adversarial reporting, continues to influence media operations in certain parts of Africa and Southeast Asia. Despite the globalization of media practices, which has resulted in a convergent news culture, international broadcasters like Al Jazeera have generated counter-flows that actively question Western dominance while still partially embracing Anglo-American professionalism ideals.

Journalism as a Capitalist Enterprise: The Structural Compromise

The critical scholarly perspective posits that journalism as a profession itself is capitalism. It developed not merely as a civic or ethical practice, but as a business enterprise deeply embedded in the capitalist production, circulation, and consumption of news. The emergence of journalism as a distinct practice, and the professional journalist as an institution, occurred in the late 19th century alongside industrial capitalism, characterized by the arrival of mass printing, the steam press, linotype, and advertising.

This embedding means that professional norms and identities are continually shaped (and in some cases undermined) by capitalist market forces. Contemporary journalism is increasingly structured by platform logic, which promotes the commodification of content. Deploying a Marxist critique, Colin Sparks highlights how media outlets are inherently embedded within capitalist ownership structures, ensuring their orientation often aligns with business interests or class power.

Complicity with Power: Filtering Facts and Empirical Failure

One of the most damning failures of this commercially driven model is its inability to generate concrete change. While global crises—such as far-right violence, armed conflicts, and environmental degradation—are rich in ‘news value’ according to Anglo-American yardsticks, they primarily serve to make attractive frontpages and generate vast amounts of multimedia content, ultimately feeding the global advertising industry.

Journalism in this paradigm is often reduced to the mere reporting of facts. However, the critical problem lies in how “facts” are sieved through the tool of ‘sources of information’. Reporters globally tend to consider information factual and newsworthy only when it has been consecrated by those in positions of power. Consequently, facts “manufactured in corridors of high power” possess greater voice and legitimacy than facts emanating from disadvantaged peoples. The prevailing paradigm does not put a premium on the pursuit of truth value when established facts are provided by powerful sources.

The consequences of this allegiance to power are evident in catastrophic geopolitical events. For example, Judith Miller of The New York Times, relying mainly on intelligence sources, published propagandistic reportage suggesting Baghdad was manufacturing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). This claim proved to be an outright lie, but not before Iraq was reduced to rubble in the shade of a military-industrial complex of which journalism was a vital partner.

Furthermore, the model exhibits indifference toward deep social realities. The indifference and inability of the Anglo-American model to address social realities like those in Gaza is striking. Associate editor of New Lines Magazine Samer Badawi highlights the limits of this reporting mandate: “Journalists are taught: Do the reporting, and the story will write itself. But how does one narrate the stories of 20,000 dead children? In their frequency over the last two years, Gaza’s individual tragedies have had a way of congealing into metaphor.” This is why, journalism must never be reduced to reporting of facts alone when facts, manufactured in corridors of high power, possess more voice than facts emanating from disadvantaged peoples.

We argue that the vocabulary of journalism within the Anglo-American fold is deeply integrated into what Martti Koskenniemi terms ‘the legal infrastructure of global capitalism.’ This legal infrastructure includes “laws—public and private, domestic and international—that regulate practically all aspects of social life by distributing rights and duties, powers and vulnerabilities to groups across the world.” Journalism plays a critical mediatizing role in making this complex matrix functional and legitimising its operations to compliant communities. Ultimately, the logic is self-reinforcing: “commercialisation dictates the nature of journalism and prescribes the limits of public interest.”

Charting Critical Alternatives

The Anglo-American journalism model, condemned to subordination by the economic rationale of marketing, perpetually functions to justify the existing order. If the dominant paradigm is structurally compromised, alternative imaginaries must be charted. One possibility, suggested by Kevin Williams, is to develop a “form of journalism, which is more literary, political and intellectual in its approach.” Structural reform is necessary to shift news production away from treating journalism merely as a commodity. Only by fundamentally challenging the commercial infrastructure that dictates the nature and limits of public interest can journalism cease to be a vital partner in the existing order, genuinely pursue truth value and change lives for better.