It is our place as journalists to lead the way in challenging oppressive social and political structures—here's how to do it

How do we begin to decolonise journalism? What role do journalists play in perpetuating societal structures that continue to empower the oppressor over the oppressed?

It may be idealistic to assume that a complete decolonisation of journalism is possible. But there are ways in which journalists can begin to challenge some of the powerful structures that perpetuate colonial dynamics.

Showing Both Sides of the Story?

We’ve seen this debate come up frequently—the need for journalists to show “all sides” of the story. It flared up during the Trump Presidency, in relation to the Black Lives Matter campaign, for example. Trump’s initial response to violent protests by white supremacists in Charlottesville in 2017 was to state that “you also had people that were very fine people on both sides.". He was roundly criticised for this statement. During his own campaign for the presidency nearly two years later, Joe Biden said: “With these words, the president of the United States assigned a moral equivalence between those spreading hate and those with the courage to stand against it.”

Similarly, we often see "both sides" rhetoric playing out in the media when it comes to the oppression of the Palestinian people by Israeli occupying forces—something that has been written about previously in this magazine. But is it really fair to ascribe a “both-sides” argument in a situation where one side is demonstrably more powerful and is acting as the oppressor of the other?

Should journalists still present all sides when we know that one side is lying or that one side is clearly the oppressor? By giving the oppressor a means to justify their oppression does journalism perpetuate the cycle of oppression? Do we really need to hear “justifications” from the police after they’ve been caught on camera murdering an innocent man? Do we really need to hear “reasons” from a colonising state about why the colonised need to be colonised?

The current standards of journalism are rooted in the belief that in order to be objective, all sides must be represented equally. But this stance is problematic because it relies on the myth of a “fair” world, where everyone has a level playing field. It ignores the power imbalances that exist throughout all areas of life and the vast difference in access to resources available to different groups.

Let’s take the example of the police in the US—an institution with access to great resources that can buy impressive PR teams to ensure better and softer representation in shows, movies, and popular culture generally. On the other hand, leaders of marginalised communities, which often suffer at the hands of the police, are scrambling for donations.

Given this inherent imbalance, is it really fair to give both sides equal space on a media platform? Wouldn’t doing that ignore the existence of structural inequity and ignore how certain communities and voices are deliberately kept out of the conversation? More often than not, this happens to be the voice of the most marginalised members of society. By giving equal weight to their voice and to the voice of their oppressors, journalism may be perpetuating these systems of violence.

Consider Your ‘Positionality’

Another issue is the “positionality” of the journalist. In an ideal world, the journalist is a neutral observer, an invisible entity that serves to collect a story and present it. The journalist is not meant to be part of the story.

But this is a myth that many journalists and media organisations continue to tell themselves. As a human being, a journalist is a product of society and their position within it. A journalist naturally has his or her own values, biases, political ideals, and aspirations.

The stories that they chose to document and recall are necessarily influenced by these internal factors. In the process of choosing to tell certain stories, a journalist is also not telling other stories. A journalist therefore gives more importance to stories that he or she deems important—for whatever reason. What is deemed important is influenced by these “internal” factors mentioned above. I know that all the stories I have told as a journalist have been shaped by my own belief systems and my political causes. I know other journalists have a similar process—we cannot help but to work in this way.

The journalist is therefore never completely separated from the story. They are a part of the story—an equal part creator of the story as much as the subjects.

Who the journalist chooses to interview, what questions are asked, and how that conversation is edited and presented are all shaped by the presence of that particular journalist.

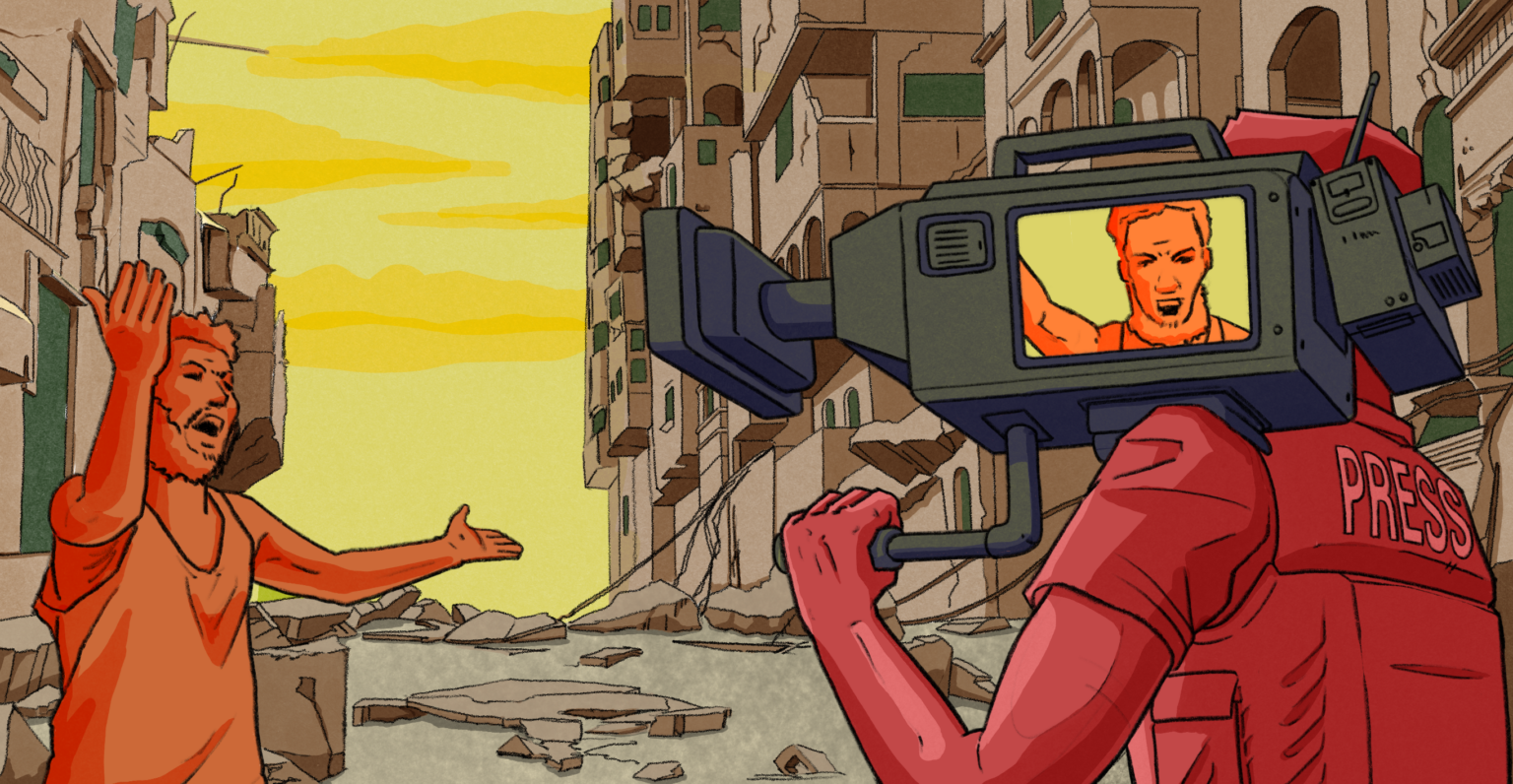

This becomes even more complex when we address the power relationship between the journalist and the interviewee. How does the ethnic and economic background of the journalist shape the interaction, the conversation, and hence the story?

I have previously written about how my being a Sunni-Muslim (part of the majority population) in Pakistan shaped how a Hindu Pakistani viewed me and responded to my questions when I interviewed him.

Similarly, what happens when a white, European reporter approaches a post-colonial society in order to interview marginalised members of that community? There is an inescapable power dynamic present that will influence not only the way an interviewee will view the journalist but also how they will choose to respond to the questions.

Media Agendas

Then there are the external factors. What are the organisational agendas encouraging a journalist to pursue a certain story? What kinds of stories from a particular area are more “saleable” or “palatable” to the audiences of specific news organisations?

In the context of Pakistan, for example, where international audiences expect certain kinds of stories to be told, we frequently see stories about gender-based violence, violence against minorities, Islamic militancy, civil-military disparity, etc.

Of course, I am not arguing that such issues don’t exist in Pakistan. I have written extensively about violence against religious minorities in Pakistan. The problem emerges when specific issues become the sole prism through which a society is viewed.

When news stories about a single issue are generated globally, a complex society is reduced to these news items of violence, and that becomes the only thing associated with the country. This sort of media coverage results in tropes, stereotypes, and orientalist clichés that are in turn used by journalists, particularly those not from the society in question.

In many ways, these tropes reflect the colonial legacy of Orientalism. For example, cases of Sunni-Shiia violence are explained away as a “centuries-old problem," as opposed to being understood in their more recent context. We also see the perennial depiction of religious minorities in Pakistan as being perpetual victims with no agency. Instead of exploring new angles and presenting less-covered aspects of a society, journalists end up re-creating and reinforcing the same images that have already been created for them.

These are just a few examples of the ways in which journalists can begin to decolonise their work. There are several other actions that also need to be taken before serious progress can be made towards decolonization—addressing the inadequacy of translation and the difficulties of putting a free-flowing, ever-evolving conversation into written words.

Perhaps the process can never be complete, and there will always be some aspects of journalism that will contain this inherent violence. However, at the core of this issue is reflexivity—a constant reviewing of our own work as journalists and evaluating what role our work plays in creating stereotypes and perpetuating violence.

If journalists are being honest with themselves by being reflective of their work and their role in creating or dismantling these structures of violence, decolonisation of journalism can begin to happen.

Haroon Khalid is an anthropologist and author

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera Journalism Review’s editorial stance

![Palestinian journalists attempt to connect to the internet using their phones in Rafah on the southern Gaza Strip. [Said Khatib/AFP]](/sites/default/files/ajr/2025/34962UB-highres-1705225575%20Large.jpeg)