This article was originally written in Arabic and has been translated into English with the assistance of AI tools and edited to ensure clarity and accuracy

The digital revolution has widened the gap between the Global South and the North. Beyond theories that attribute this disparity to the North's technological dominance, the article explores how national and local policies in the South shape and influence its narratives.

The acquisition and monopolisation of data have become arenas of competition among nations and significant indicators of dominance and superiority. This is evident in fields such as military industries, technology, or scientific domains like medicine. The importance of this monopoly is not limited to the pursuit of dominance alone but also extends to ensuring continued reliance on data monopolists.

The global North adopted policies of monopolisation in its dealings with data and regulated the flow of data across borders. While it is true that data flows in both directions at an unprecedented scale, the North continues to dominate. This dominance extends to control over global networks and their affiliated media, which consistently generate universalist perceptions at the expense of multicultural perspectives.

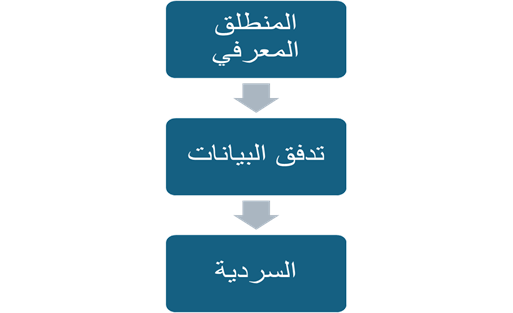

Control over data flows is not limited to issues of media consumption, economics, or culture. It forms part of a series of hegemonic practices rooted in epistemological foundations that shape the nature of data flows and the narratives that emerge from this interaction. Wars present an opportunity to reassert hegemony in its most blatant forms, which is clearly demonstrated following the military operation conducted by Hamas on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent genocidal war waged by the occupation against Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and later in Lebanon. However, this was preceded by the establishment of a narrative built on highly selective data flows originating from epistemological premises:

Southern narratives have not been undermined solely by the unbalanced cross-border cultural flows between the North and the South but also due to purely Southern factors. This article argues that the dominance of data flows from the North to the South is not only a result of the North’s advancement in media and communication or its monopoly over digital technology but also stems from national and local policies within Southern countries.

Capitalism, Media Consumption, and Globalisation

The global information and communication system emerged after 1945 within the context of global colonialism. Its primary aim was to facilitate communication between colonial powers and their distant colonies in Asia and Africa. The information and communication infrastructure, both then and now, was primarily designed to serve the "needs of the empire" (1).

Voices began advocating for the principle of free information flows as a strategic objective. One of the most significant documents addressing this issue was the 1980 UNESCO report by the McBride Commission, titled "Many Voices, One World: Towards a New, More Just and Effective World Information and Communication Order" (2). It includes justice and fairness, reciprocity in information exchange, reducing reliance on one-way communication flows (from the North to the South), ensuring bidirectional data and communication flows, and securing the right of "developing countries" to establish independent national media systems free from the monopoly of transnational capitalist media while emphasizing self-reliance and cultural identity.

The global information and communication system emerged after 1945 within the context of global colonialism. Its primary aim was to facilitate communication between colonial powers and their distant colonies in Asia and Africa. The information and communication infrastructure, both then and now, was primarily designed to serve the “needs of the empire"

However, these international calls did not affect the North’s dominance over data flows, achieved through two key mechanisms:

1. Cultural Globalisation Serving Capital:

The Western approach to media and data flows has been centrally focused on capitalist media, which has evolved into what we see today. The technological advancements related to data flows have significantly accelerated technological breakthroughs, mass media obsession, transnational corporations, and internet-based news and entertainment sites (3). This has come at the expense of local culture, oral traditions linked to local communities, folklore, and small-scale initiatives with modest funding.

Capitalist media does not account for national boundaries because it operates outside the logic of borders. Global and national media corporations heavily invest in the international media economy, the trade of media commodities, and audience sales to advertisers. It has led to a restructuring of local cultures in favour of unidirectional and monolithic values, detaching local culture from its roots.

2. Dominance Over Data Flows to Control Narratives and Entrench Hierarchies in Global Politics:

This phenomenon can be seen as a legacy of colonialism and its aftermath. Colonial powers exert “epistemic violence,” a concept introduced by Gayatri Spivak (4), which involves erasing the pathways connecting local groups, including their traditions, customs, and knowledge systems, by obliterating the original history of the land and its people.

“There is dominance over data flows with the aim of controlling narratives and consolidating hierarchical structures in global politics, framed as a legacy of colonialism and its aftermath. The (dominant) colonial powers exercise epistemic violence, a concept coined by Gayatri Spivak.”

The dominance over data flows directly influences narrative control. The ability to shape narratives - or to suppress the formation and emergence of alternative narratives - is crucial for culture and imperialism (5). In contrast, a significant portion of Western media does not source its reports from the ground or engage with local narratives but relies on preconceived notions derived from the writings of Orientalists (6).

Euro-American modernity has developed a “cognitive framework through which meaning can be constructed and the production of new knowledge directed” (7). Its influence extends beyond news, films, TV series, and books. This was evident after 7 October 2023, when a new framing of the Palestinian issue emerged, starting from this date and blaming Palestinians while disregarding their plight. The ongoing violence perpetrated by the Israeli occupation against Palestinians tends to remain invisible in Western media. Similarly, the daily suffering of Palestinians under occupation fails to surface unless it is framed as a sudden eruption, disconnected from the context of occupation, and quickly reframed as an isolated, transient incident.

The South and Data Localisation

One of the key issues in the South’s handling of data flows from the North is the tendency to localise rather than resist them. The first factor relates to the removal of colonial residues from Southern minds, which remain entrenched in Western centralism. As Molefi Asante reminds us, much of what Africans, Asians, and Latin American scholars have written has been added to European literature. Even the South’s critique of the North has often been framed from a European perspective. What the South needs, he argues, is a way to prevent the erasure of Southern scholars and their histories (8).

The second factor is that the global South cannot be considered homogenous; it encompasses a wide range of cultural diversity. Nonetheless, a common and intersecting feature of the global South is its deep-rooted adherence to liberal traditions. Despite attempts to create indigenous regional theories, no part of the global South can claim sovereignty or liberation from Western models and knowledge in its theoretical and intellectual projects (9). There has been an implicit tendency to view Western cultures from the perspective of a student.” In contrast, Western academics approach “non-Western cultures from the perspective of a teacher” (10)

Despite attempts to establish local or regional theories, none of the Global South can claim sovereignty or liberation from Western models and knowledge in its efforts to develop its theories and frameworks of understanding.

“One may speak of media and communication studies around the world, yet the discussion is essentially an intellectual monologue with the dominant West, speaking to itself” (11).

The third factor is the role of the state and elites. Communication professor Colin Sparks highlights this in his study titled Reviving the Imperial Dimension in International Communication. Sparks argues that while borders may be envisioned as melting pots of cultures, they simultaneously serve as contentious spaces marked by deeply rooted social contradictions. These contradictions enable newer forms of cultural imperialism, often facilitated by the co-optation of states and their elites by colonial powers (12).

Moreover, Spivak addresses key barriers that obstruct the ability to articulate and narrate these stories, such as linguistic barriers, cultural biases, and power dynamics imposed through colonialism and imperialism (13).

The Global South represents an epistemic and interpretive framework grounded in the struggles of those who endured slavery, colonialism, and capitalism. It is a space for self-realisation, functioning as part of an epistemological project aimed at rehumanising, rewriting, and liberating identity.

The fourth factor lies in the Global South’s growing consumption of transnational Western products, particularly entertainment and leisure media, crafted with advanced technological and digital expertise. This has not only contributed to their widespread popularity but also reinforced the dominance of capitalist ideology, shaping perceptions of various issues through the lens of the producing corporations.

Strategies for Resistance from the South

The Global South must create the necessary conditions to regain its narrative with the momentum required to establish an epistemic centre equivalent to the North’s hegemony. Nevertheless, this does not preclude adopting a set of strategies aimed at reducing the impact of Northern data flows while simultaneously creating space for the narratives, knowledge, and data of the Global South.

In this context, the Global South represents an epistemic site and an intellectual framework grounded in the struggles of those who have endured slavery, colonialism, and capitalism. It is a space for self-realisation as part of a knowledge project aimed at rehumanising, rewriting, and liberating identity. Conceptually, the Global South is not merely a geographical entity but a non-geographical space of intellectual resistance against marginalisation and exclusion.

One of the key strategies for resistance lies in creating Southern narratives. For Homi Bhabha, “the true nature of narrative” involves raising questions about differences, power dynamics, and contradictions from cultural and political perspectives (14). Narratives do not merely depict knowledge and ways of life from elsewhere; they also build, invent, and produce imagined territories. When attention shifts away from old models of power and the South begins to explore ways in which narratives can be rooted and flow differently, it creates a new kind of global culture that does not necessarily depend on the North (15). The modern revolution in digital communications presents a golden opportunity for the Global South. There are multiple creative ways to shape narratives through data, leveraging the opportunities offered by digital platforms to expand reach and influence. Such practices allow the Global South to continually renegotiate its position between the margins and the centre, thereby reclaiming its epistemic authority. These narrative practices disrupt dominant discursive and visual domains, generating new pathways for knowledge production.

The essence of data flow’s impact lies in the power and epistemic foundations behind these flows and their role in creating hybrid spaces within national borders. These spaces convince Southern populations that globalisation and the romanticisation of transnational cultural flows will not affect their local cultures. However, the reality is different, as multinational Western corporations and consumer-based mass cultures dominate these data flows. Nonetheless, digital advancements offer the Global South (both geographic and epistemic) an opportunity to craft counter-narratives to challenge hegemonic ones.

The Global South, as an epistemic site and non-geographical space, has played a crucial role in supporting the Palestinian cause, particularly after 7 October 2023. The South disrupted long-standing narrative arrangements centred around concepts such as peace talks, negotiations, and transitional justice. It reframed the Palestinian issue within the contexts of the 1948 Nakba and the 1917 Balfour Declaration. This shift led to several international institutions adopting the Palestinian narrative, culminating in a significant triumph for the Global South: dismantling Western imperialist-centred narrative monopolies, such as framing events through terms like “genocide.”

This epistemic and discursive shift exemplifies how the Global South has actively reshaped global discourse, asserting its capacity to challenge and transform dominant narratives while advocating for justice and equity.

References

- Last Moyo, The decolonial turn in Media Studies in Africa and the Global South. (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p.134.

- McBride Commission, Many Voices One World: Towards a New, More Just and More Efficient Information and Communication Order. (Paris: Unesco. 1980)

- John D. H. Downing, Where We Should Go Next and Why We Probably Won’t: An Entirely Idiosyncratic, Utopian, and Unashamedly Peppery Map for the Future. In Angharad N. Valdivia (Ed.), A Companion to Media Studies. (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), p.500.

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the subaltern speak?”, in: Peter H. Cain, Mark Harrison (Eds.), Imperialism: Critical concepts in historical studies. Volume III. (Abingdon: Routledge, 2023).

- Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture, (London: Routledge, 1994).

- Edward Said, Orientalism, translated by Muhammad Asfour (Cairo: Dar Al-Adab Publishing, 2022).

- Walter Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs. Princeton, (NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), p.18.

- Molefi Kete Asante, “The Ideological Significance of Afrocentricity in Intercultural Communication”. In Molefi Kete Asante, Yoshitaka Miike, and Jing Yin (Eds.), The Global Intercultural Communication Reader, (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), p.51.

- Last Moyo, The decolonial turn in Media Studies in Africa and the Global South. (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

- Molefi Kete Asante, Yoshitaka Miike, and Jing Yin, The Global Intercultural Communication Reader, (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), p.3.

- Georgette Wang, De-Westernizing Communication Research: Altering Questions and Changing Frameworks.) London: Routledge, 2011), p.2.

- Colin Sparks, “Resurrecting the Imperial Dimension in International Communication”. In C. C. Lee (Ed.), Internationalizing “International Communication”, (Michigan: Michigan University Press, 2015), p.158.

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the subaltern speak?”, in: Peter H. Cain, Mark Harrison (Eds.), Imperialism: Critical concepts in historical studies. Volume III. (Abingdon: Routledge, 2023).

- Homi Bhabha, Nation and narration, (London: Routledge, 1990), p.312.

- Mehita Iqani and Fernando Resende, Media and the global south: Narrative territorialities, cross-cultural currents, (New Delhi: Routledge India, 2020), p.14.

![Palestinian journalists attempt to connect to the internet using their phones in Rafah on the southern Gaza Strip. [Said Khatib/AFP]](/sites/default/files/ajr/2025/34962UB-highres-1705225575%20Large.jpeg)