Mauritania holds the top position in the Arab world in the Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders. However, behind this favourable ranking, the media and journalists face significant challenges, chief among them the ambiguity surrounding the definition of a "journalist" and the capacity of media professionals to fulfil their roles in accountability and oversight. Despite official efforts, the defining feature of Mauritania’s media landscape remains its persistent state of fluctuation.

To the outside observer, Mauritania’s media landscape may appear vibrant and promising. The country continues, despite recent setbacks, to rank highest in the Arab world in press freedom, according to Reporters Without Borders.[¹] Official rhetoric praises steady strides toward institutionalisation and professionalisation. The sector boasts a plurality of media outlets, a growing number of journalists, and a proliferation of syndicates defending press freedoms. Yet behind, or perhaps alongside, this polished image lies a very different reality. The country’s media scene is caught in a state of persistent and disorienting flux, making any definitive judgment vulnerable to miscalculation unless all dimensions of the picture are considered.

A Landscape of Numbers

A recent survey[²] conducted by authorities between November 18 and December 5, 2025, reveals a sprawling media ecosystem: 4 public media institutions, 250 online news platforms, 66 print newspapers, 11 audiovisual channels, 10 international correspondents, 4 representatives of conditional universal access agencies, 62 Facebook-based media platforms, 15 audiovisual production agencies, and 27 press unions or associations. The latest membership records from the Syndicate of Mauritanian Journalists, the country's largest professional media union, show more than 1,700 registered members, in addition to lists of affiliates from other unions and associations.

These figures become even more striking in the context of a country with a population under 5 million, an adult illiteracy rate exceeding 40%, and internet penetration estimated between 65% and 70%, according to official statistics.[³]

A Young Experiment

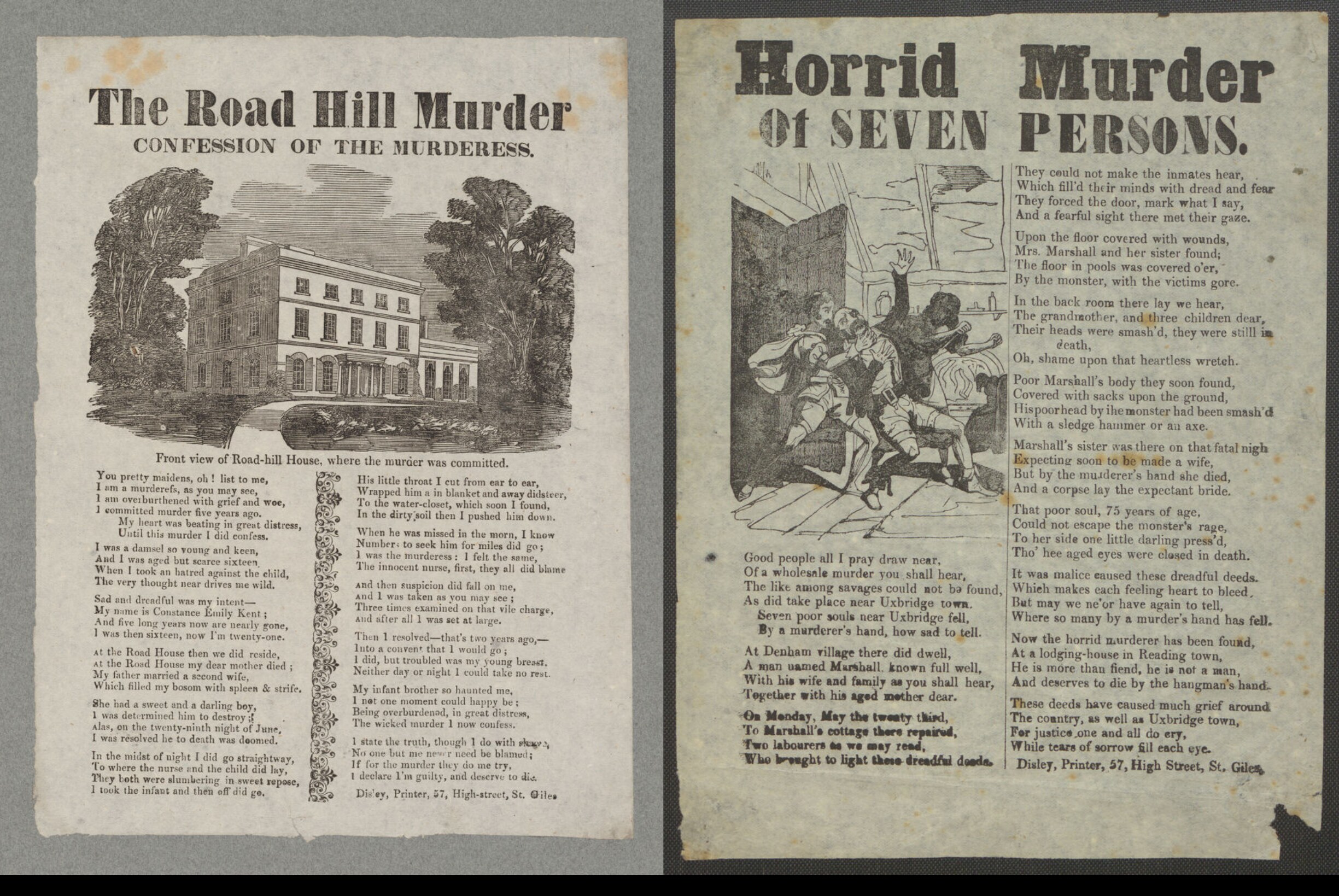

Mauritania’s independent media experience is relatively recent, especially compared to other Arab and African nations whose media institutions emerged immediately after independence or even prior. The country's independent media is only just completing its fourth decade, having emerged in the late 1980s amid preparations for a multi-party political system, culminating in the 1991 Constitution adopted on July 20.

This fragile experiment has seen advances and setbacks. The 1990s and early 2000s were marred by frequent newspaper confiscations. However, the transitional period of 2005–2007, following the fall of President Maaouya Ould Taya’s regime, marked a turning point.

Each successive regime has tried to leave its imprint on the media sector. Under President Ould Taya (1984–2005), independent media began to take root. During the short transitional period under Colonel Ely Ould Mohamed Vall (2005–2007), press freedom surged. Pre-publication censorship was abolished, media licensing was transferred from the Interior Ministry to the judiciary, the law permitting newspaper confiscation was repealed, and the High Authority for Press and Audiovisual (HAPA) was established. President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz (2008–2019) initiated the liberalisation of the audiovisual space by authorising private radio and TV stations; a shift from the earlier focus solely on newspapers and online platforms. Despite challenges, this period left a lasting imprint on the media landscape.

Reform Committee and Repeated Promises of Professionalisation

In June 2020, just months after assuming power, President Mohamed Ould Ghazouani formed a national media reform committee tasked with diagnosing the state of journalism in Mauritania and presenting proposals for a comprehensive overhaul of both public and private sectors.[⁴] The president reminded the committee members of the gravity of their mandate.

Following extensive consultations with experts and media professionals, the committee issued a report describing the state of media in the country as “extremely dangerous,” warning that its negative impact on both state and society had become undeniable. It argued that the prevailing “chaos, impunity, and corruption” could be traced directly, or at least indirectly, to media failure.

The report concluded that the Mauritanian media was "a far cry from successful journalism." Despite the proliferation of public and private outlets and the presence of correspondents across the country, the media had little substantive impact on the public. It was detached from its educational and developmental role and failed to engage with real societal issues. It neither practiced constructive criticism nor employed investigative journalism to expose corruption, deceit, or inefficiency. Instead, it often served as a cover for failure, avoiding the messy realities of life in the streets, markets, schools, mosques, and transportation sector.

The committee proposed 64 recommendations[⁵] across eight areas: national media policy, institutional structure, legal frameworks, human resources and training, funding and financial sustainability, content quality, technical infrastructure, and new media.

Fragmentation and the Flight of Talent

One of the most persistent obstacles facing the media sector is its fragmentation and dilution, which have rendered it unattractive to qualified professionals.[⁶] A vast number of individuals hold licenses for media outlets and often enjoy prominence at official events, despite lacking even basic professional competencies.

This dysfunction has reached the point where individuals with no literacy have entered the media field. Many so-called "media institutions" are nothing more than a few papers in a briefcase, yet their holders compete alongside legitimate journalists for recognition, access to events, and shares of the public subsidies allocated to the private press, sometimes with greater success.

This reality stems primarily from the non-enforcement of existing laws, especially those defining who qualifies as a journalist, the conditions for obtaining a press card, and the legal requirements for practicing journalism. While there have been periodic efforts to implement these rules, most recently just weeks ago[⁷], they often stall midway.

Reporters Without Borders diplomatically captured this situation, noting that Mauritanian journalists remain vulnerable due to what they termed “survival journalism”,writing articles or producing reports in exchange for modest payments. Despite the availability of public subsidies for media, poor management and oversight prevent economic stability.[⁸]

To address this, the HAPA proposed a comprehensive plan that incorporates three key elements: enforcing existing legal provisions, completing the framework for issuing press cards, and revising how public subsidies are allocated. The authority also recommended forming a joint committee with the relevant ministry to implement this plan between 2025 and 2028.

Liberalisation Delayed

As efforts to regulate the print and online press faltered, the audiovisual sector fared no better. Regulatory failures and structural challenges drained it of its intended purpose. Several outlets ceased broadcasting altogether or shifted to pre-recorded content, disregarding licensing obligations.

The audiovisual liberalisation effort began in 2011 with the licensing of five radio stations and two TV channels, followed by three more TV stations in 2013. In the past three years, three additional channels have been licensed.

As of today, only these three newest channels operate legally and consistently. Of the earlier ones, six have either expired licenses or have halted operations entirely. The remainder operate without renewed permits.

Public media institutions like Radio Mauritania and Mauritanian Television have yet to sign the mandatory charter with HAPA or establish formal service agreements with the government.

A recent survey by HAPA paints a sobering picture: Mauritanian Television employs 885 people, but only 204 have official contracts. Radio Mauritania employs 1,078 workers, of whom only 180 are formally contracted. The official news agency employs 416 people, with 262 under contract. In contrast, all private radio and TV stations combined employ only 241 workers, with 151 contracted.[⁹][¹⁰]

In response to this precarious institutional environment, authorities have delayed regulations concerning community-based broadcasting channels, citing the overall dysfunction of private news outlets.

Fluctuating Freedoms

This instability is perhaps most evident in the area of press freedom, both in terms of on-the-ground realities and international rankings.

Field journalists often face harassment from security forces while on duty, including physical assaults and confiscation of equipment. They also encounter formal and informal pressures aimed at obstructing investigations into corruption and governance failures.

This is reflected in international press freedom indices. In the latest Reporters Without Borders ranking, Mauritania fell 17 spots in a single year, from 33rd to 50th, losing its lead among African countries but retaining the top spot in the Arab world.

Mauritania’s history with press freedom rankings is a long and erratic one. Over the past two decades, the country has fluctuated between top-tier positions and steep declines. Between 2005 and 2025, it ranked 50th or higher only four times. In most other years, it fell far lower, sometimes beyond the 100th rank.[¹¹]

Conclusion

Mauritania’s media landscape possesses latent strengths that, if properly harnessed, could support a successful and dynamic press environment. Yet these assets are undermined by deep-rooted weaknesses and structural dysfunctions that place the entire enterprise at risk. Without serious reforms, this fragile experiment in press freedom may fail to reach its full potential.

Sources

- Reporters Without Borders. “Mauritania.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://rsf.org/ar/البلاد/موريتانيا

- Al Jazeera Media Institute. “Trainer Application Form.” Jotform. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.jotform.com/231545029583054

- Ansade. “2023 General Population and Housing Census.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://ansade.mr/ar/النتائج-النهائية-للتعداد-العام-للسكا/

- Essirage. “Committee Appointed July 20, 2020.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://essirage.net/node/20228

- Al Akhbar Info. “Highlights of the Recommendations.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://alakhbar.info/?q=node/31256

- Ahmed Sidi. “Digital Journalism in Mauritania: The Difficult Beginnings.” Al Jazeera Media Institute. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://institute.aljazeera.net/ar/ajr/article/1549

- Sahara Media. “Formation of the Press Card Committee.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://saharamedias.net/248134/

- Reporters Without Borders. “Mauritania.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://rsf.org/ar/البلاد/موريتانيا

- HAPA’s National Media Survey, 2025

- Recent government initiative on media workers' contract regularisation

- Ahmed Mohamed Al-Mustafa. “How to Understand Mauritania’s Top Press Freedom Ranking?” Al Jazeera Media Institute. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://institute.aljazeera.net/en/node/2663